If you had seen me walking into my doctor’s office on the morning of May 18, 2015, your first thought wouldn’t have been, “That fat dad sure needs to lose some weight.”

I’m 5-foot-10, and when I woke up that morning I weighed 176 pounds. By the time I got on the doctor’s scale, fully clothed and fed, I was all the way up to 179. That put my body-mass index at 25.7, which is why I left the office with a pamphlet describing how to make healthy food choices and instructions to keep my BMI at or below 25.

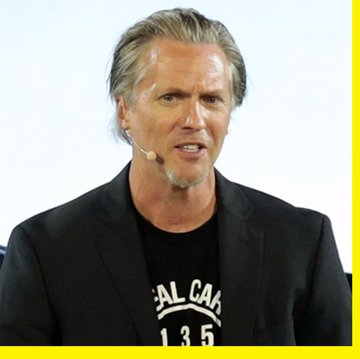

Mark Peterson, PhD, can relate. As a professor and exercise physiologist at the University of Michigan Medical School, he works with a wide range of age groups, and knows as well as anyone which statistics really matter. “I’ve always hated BMI,” he says. “It can’t detect who’s at high risk.”

That’s because, as noted in the article The Problem with BMI, it’s just an equation. It can’t tell the difference between Dwayne Johnson and Fat Elvis. But Peterson isn’t worried about lean, strong athletes being misclassified as overweight or obese. (His own BMI is 27, thanks to a lifetime of lifting.) The real problem is when people with a high body-fat percentage and low muscle mass are classified as “normal” and “healthy.”

“That’s the worst-case scenario—people who’re at high risk because they have no muscle on them,” he says.

Peterson is the author of a new study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine that shows a much better way to assess someone’s risk for future health problems: handgrip strength. “Higher grip strength is a reflection of greater robustness,” he says. “It’s a proxy indicator for overall strength.”

It’s also easy to measure and relatively cheap, as medical equipment goes. The instrument he used, called a handgrip dynamometer, retails for $350. A patient squeezes it several times with each hand, and the doctor records the highest score. “It’s almost foolproof,” he says, and it gives you “a nearly perfect snapshot of someone’s strength capacity.”

Researchers have studied the link between strength, health, and longevity for decades. Grip strength was originally used to test frail, elderly people in nursing homes to see which ones were malnourished. (The stronger ones were assumed to be eating enough.) It was also a useful way to predict which patients about to undergo surgery would have the longest recovery and the most complications. Eventually researchers linked a weak grip to a higher risk of death from any cause.

More recently, studies have linked strength and health in surprising ways. One of Peterson’s studies, published last year in Pediatrics, showed that the strongest sixth graders had the lowest risk for metabolic syndrome, a cluster of symptoms leading to heart disease and diabetes. And a study of Swedish army recruits from the ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s showed that the weakest were at highest risk for premature death from any cause. The strongest were 35 percent less likely to die from cardiovascular disease and 20 to 30 percent less likely to commit suicide.

Related: 10 Facts You Must Know about Heart Disease

In Peterson’s current study, he and his coauthors collected grip-strength data from more than 7,000 Americans from 6 to 80 years old. They then charted how strength rises and falls through that age span.

Absolute strength peaks from 25 to 35. By age 50, the average guy will be a little weaker than he was at 20. At 80, he’ll have slightly less strength than he did at 14. But Peterson cautions that absolute strength doesn’t matter nearly as much as strength adjusted by total body mass. “Pound-for-pound strength is a better predictor,” he says. “You want to be strong for your weight.” (If you’re looking for a program that builds strength and burns fat, try The Anarchy Workout. One guy lost 18 pounds of fat in 6 weeks.)

By that measure, a guy’s relative strength will be about the same from his teen years until his mid-40s, although it will still peak in his late 20s.

Another caveat is that the data doesn’t apply to serious lifters. For them, a grip test would only measure the strength of their hand and forearm muscles. But Peterson estimates that this applies to less than 10 percent of the population.

For everyone else, handgrip strength offers a surprisingly accurate prediction of the odds for survival into old age, even if it’s impossible to say whether strength itself makes people healthier, or if healthier people are simply stronger. Peterson thinks it’s probably some of both. “People who’re involved in exercise throughout life will tend to be stronger,” he says. “They probably did something that preserved their fitness and health.” (For more tips on how to live longer, check out 5 Ways to Add 22 Years to Your Life.)

People like you and me, in other words. If nothing else, routine strength testing might keep our doctors from telling us we need to lose weight until they know what we can do with the weight we already have.

Lou Schuler is an award-winning journalist and the author, with Alan Aragon, of The Lean Muscle Diet.